A LOOK AT WHERE WE STARTED

Long before adventurous sailors like Cook, Vancouver, and Quadra charted the waters of the West Coast in the late 1700s, the cedar dugout canoes of the First Nations people paddled the clear waters of Hakai Pass. While these first inhabitants left little visible remains, there is still a distinct mystical quality to the area.

In this century, several generations of commercial fishermen jealously guarded the secret of the abundant salmon and halibut found in these rich waters. They also drank in the beauty from their quiet anchorages in the many protected coves of Hakai Pass.

Our Club was started in 1970 when three friends headed north from Rivers Inlet exploring new fishing areas. They anchored their boat near the present camp location. It didn’t take them long to realize the incredible potential of Hakai Pass. When the friends returned to Vancouver, they began a process of securing a land lease from the Provincial Government. Others soon joined in their dream. The beginnings were humble, but season by season a camp was hewn out of the wilderness. We are thankful for the hard work and determination of early Club members who built the Club to what it is today.

History of Hakai

Land & Sea FISHING CLUB

—— By Phillip Chutter ——

Hakai Passage was “discovered” in July 1969 by Philip Chutter, John Clark and George Davenport. They had been fishing in Rivers Inlet but were chased out by the killer whales who invaded in great numbers thus ruining the fishing.

They decided to try the place called Hakai up the coast. The weather was terrible, it was raining hard, coupled with a 40 knot wind. It was too rough to fish, so we (there were 12 of us) played cards, etc. John, George and I decided to row ashore and see what the white beach was all about. It was beautiful and we decided that on our return to Vancouver we would see who actually owned the land.

We were told that it was Crown Land but that we could obtain a 20 year lease for 100 feet of waterfront each. We flew back to Hakai with a tape measure and found that the waterfront measured 1400 feet. This meant that to lease the whole of the waterfront we would need 12 additional people and so we set out to find 12 “gentlemen” fishermen and were most successful. The next step was to post the land using the proper forms, giving names, citizenships, dates of birth, etc.

We flew back up to Hakai and placed 14 posts each bearing the name of the person applying for a lease. It was then necessary to gazette our applications (i.e. publish in every newspaper from Prince Rupert to Vancouver a copy of our application). Eventually our persistence paid off and we were advised that our applications were approved subject to having the leases surveyed. Our pilot Gordon Skelton flew the surveyors to Hakai and made a second trip to bring in their equipment, food, etc. (one of the surveyors was a huge man weighing over 220 pounds – we wondered how he would ever get up those hills). It was then decided to form an association comprising the 14 landholders. Thus was born the Hakai Land and Sea Society.

Planning the new camp and arranging to get the supplies to camp took a considerable amount of time but Island Tug came to our rescue. Art Elworthy agreed to send all the supplies that we required to the site on one of their tugs on or about August 1, 1970. John Clark and I bought a 20 foot Sangstercraft Inboard/Outboard boat with a hard top cabin which we named the Aquarius – John Usborne offered to drive it up to Hakai with our start-up supplies. What a load that was!! The swim grid was under water. John left Vancouver harbour three days ahead of us (the work party). We sent three people up to Port Hardy on commercial aircraft and three of us, including pilot Gordon flew in the Cessna. The timing was perfect. John Usborne, after having to spend three hours tied up behind the Storm Islands to wait for the fog to lift, arrived at the site about noon, we were about an hour ahead of him. Gordon Skelton made two trips to Port Hardy to pick up the rest of the crew. In the meantime we set up two tents on the south side of the point and built a fire and only just in time because it started to rain. During the night the weather worsened, the wind picked up, and the rain increased. At about 2:00 AM our tent blew down and shortly later the other tent blew down. Our pegs holding the tent down would not hold in the sand, what a mess, every one of us was soaked, our sleeping bags were wet and everything was permeated with sand. We were glad to see the daylight when it arrived. Cheerful John Usborne cooked up a fine meal of bacon and eggs and lots of hot coffee on two Coleman stoves.

The day was spent clearing a space and making a foundation for two large tents. We had a chainsaw, a cable come-along and strong backs. While the clearing project was proceeding, John Usborne was keeping the bonfire going and trying to get our sleeping bags dry. The next day the tug arrived with plywood, 2 x 4’s, two 10' x 14' wall tents, cook stove, a 2 kw lighting plant, 8 barrels of gasoline, outboard motors, boats, a metal shower stall, and many other items.

We built two 10' x 16' platforms with a walkway between them and then built 4 foot walls to fit the canvas tents. Then tent flies were installed and the shower was installed on the platform between tents. One tent for sleeping and the other was a combination kitchen/dining room and gathering place. We installed a wood burning range, a sink and counter, a refrigerator, shelves, lights, a homemade table, benches and even a Playboy magazine rack. It was unbelievable but we were ready for guests on the third day, including an outhouse and a garbage pit.

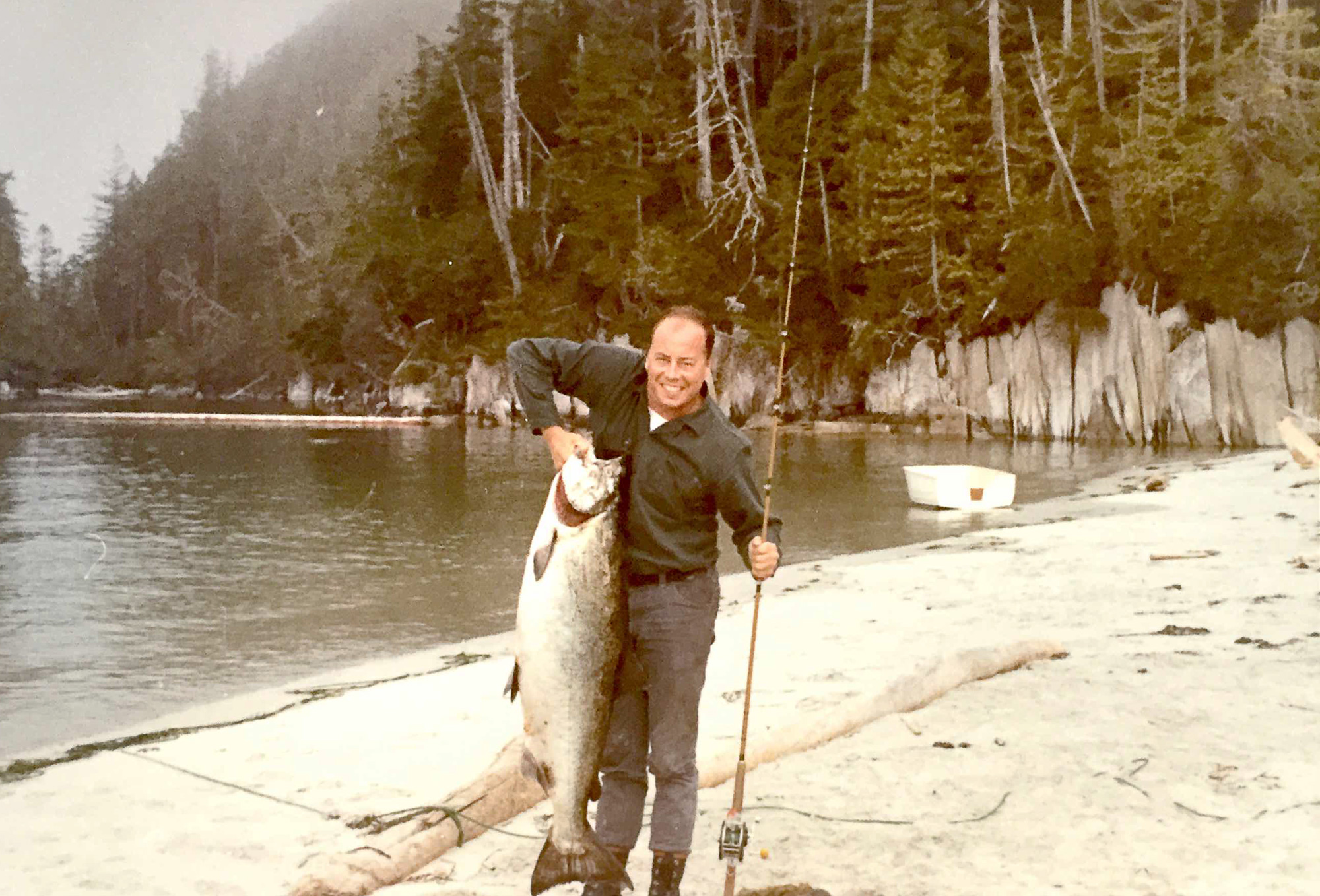

The work party actually caught some very fine salmon in the 40 pound size. The tents were used for several years. Around the third year we extended the cook house and built a proper roof and walls, thus doing away with the canvas. We also installed a diesel generator and another deep freeze. The next year a new sleeping room was built, septic tank installed, etc. We thought that the building was burglar proof as the doors were barred and bolted on the inside with the last person leaving by way of a trap door in the floor, but the thieves merely took a chain saw and cut the door in half and stole one of our boats. The next year we fastened strips of steel on the inside of the door and this time the thieves cut a hole through the roof. We decided then to store our assets somewhere else.

The following year a new and larger diesel set was installed, the electric wiring was upgraded to comply with the code and a new Garland electric cook stove and another hot water tank were installed.

When the new diesel was installed it was decided to build a proper power house combined with a drying room to dry life jackets and clothes. Dave Manning and another construction man were given the task of making cement floors and a cement sidewalk. The method they used was different but it worked. Their procedure was, first a layer of sand, then a layer of cement then a sprinkle of water, rake this all together, then repeat the procedure until the correct thickness was obtained. I’ll bet this procedure was never used on any of their construction projects BUT it worked and didn’t take too long.

The largest chinook landed during the first ten years of operation was caught by a guest. It was too heavy for our scales so the chap who caught it, cleaned it carefully, leaving the head intact, except for the gills. The fish was then wrapped in kelp and buried in the wet sand. The next day the fish was flown to Vancouver, along with its catcher. It weighed 61 pounds after arriving at the seaplane base. Innards, gills, and blood loss account for about 15% of a salmon’s body weight so it is likely this fish weighed over 70 pounds when caught! The next largest chinook reeled in during the first ten years was caught by Peter Chutter and weighed just over 59 pounds.

The best one-day fishing during the first ten years was when seven chinook salmon were caught in one hour, all within 200 yards of our beach and all weighing over 40 pounds with only three boats fishing. It was an exciting spectacle. The bay was full of needle fish. You could look over the side of the boat and see these huge salmon swimming through the needle fish schools with their mouths open. We took pictures of that day’s catch and it has never happened again to my knowledge.

Philip Chutter resigned as President of the Society in 1980 because Wright’s Canadian Ropes was sold and he was moving to the Interior to live. My last project was the building of a large float constructed from two long pipes.